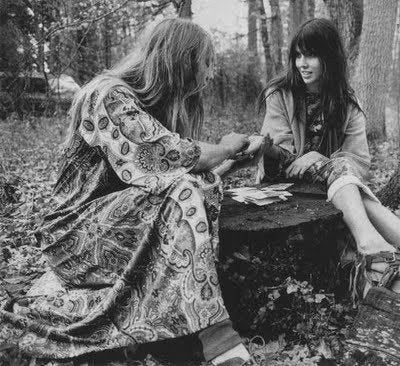

Fortune/Telling

A deeper view of divination . . .

In Connecting with Tarot, I shared a little personal history — including my most unforgettable Tarot experience: reading for hundreds (literally!) of strangers, over three beautiful summers spent as the resident fortune-teller for Scarborough Renaissance Fair…