The Esoteric Tarot: Backgrounds left off at a consequential moment in Tarot history. The ambitious origin story created by Antoine Court de Gebelin in 1775 had set the stage for a complete transformation of the Tarot.

Almost overnight, the Tarot cards were swept out of the Renaissance, into the Enlightenment — and beyond.

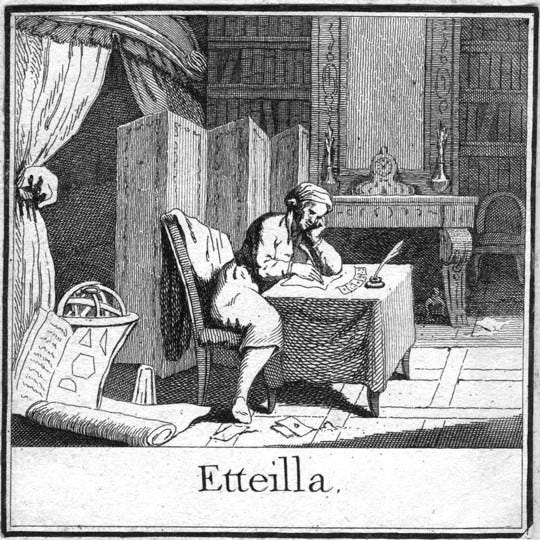

Enter Etteilla

Court de Gebelin himself was a man of serious ideas and good repute, who numbered among his friends the American polymath Ben Franklin. And although his ideas about the Tarot were based on some false assumptions, they were significant. By attempting to apply the anthropological and archaeological knowledge of his own time to an analysis of the Tarot, he revealed something of its potent symbolic nature.

But predictably enough, serious ideas about Tarot would soon be diluted and popularized — in part through the activities of a professional fortuneteller who styled himself “Etteilla” (the reverse spelling of his real name, Alliette).

Etteilla had been using an ordinary piquet deck for his cartomancy, but he readily switched to the Tarot. And by 1783 he had published a book containing his own interpretation of the Tarot cards and their origin, along with illustrations for a “rectified” (that is, esoterically renumbered) deck.

Though Etteilla’s use of the Tarot was certainly profit-oriented, he was not — as often portrayed — a charlatan. In fact, he laid the foundations for Tarot-reading as we know it today.

As Tarot historian Sherryl E. Smith points out:

Etteilla was the first to use reversals, to lay cards out in spreads, to read the cards as a continuous narrative, and the first to publish divinatory meanings. He ran a school of astrology and tarot and published the first book on how to read tarot.

The deck he created, known as “The Grand Etteilla,” differed significantly from previous Tarots. His pack included cards (such as “Fire,” “Air,” “Water,” and “Earth”) that had no counterparts in the traditional Tarot, and many of the traditional card names were changed radically. The Chariot, for example, became “Dissension,” and The Lovers was renamed “Marriage” — which certainly puts a different spin on the images.

So Etteila’s signature creation was essentially a fortune-telling deck, loosely based on the historic Tarot.

At the same time, however, Etteilla was a passionate supporter of the Egyptian hypothesis. And he embellished that myth with many new “details,” such as the date of the Tarot’s creation (171 years after the Flood), and the manner in which it was created — by seventeen magi, working under the direction of Hermes Trismegistus in a temple three leagues from Memphis!

Etteilla was the last Tarot enthusiast who could hope that confirmation of his theories might emerge from the Egyptian ruins. In 1799 — just eighteen years after Court de Gebelin published his ideas on Tarot — the Rosetta Stone was discovered. It contained the translation of a text from “mysterious” Egyptian symbols into ordinary ancient Greek.

And soon enough, the hieroglyphic language of Egypt had been decoded . . .

Gypsy Lore

As the secrets of exotic Egypt began to be unraveled by philologists, no Tarot links came to light. There was just nothing at all, despite many efforts to find some sort of connection.

But even though facts did not support the idea of an Egyptian origin for the Tarot, this romantic notion proved surprisingly durable. And it was given an imaginative boost with the introduction of yet another Tarot myth, in an 1857 book by J. A. Vaillant about the Romany people.

Vaillant was a great student of the Romany, and when he became interested in the Tarot, he immediately fancied a connection between the two.

The tribes of the Romany were called “Gypsies” in Europe exactly because they were thought to have been descendants of the ancient Egyptians — and so the idea that Gypsies had borne the Tarot with them on their wanderings fit perfectly into the still-popular scenario of an Egyptian origin.

The Gypsy hypothesis was roundly criticized as early as 1869, when Romain Merlin pointed out that there was reason to believe four-suited playing cards had been in Europe before the historical date of the Gypsies’ arrival. Since the Tarot was, in Merlin’s day, thought to have always been a seventy-eight-card deck, composed of both trumps and suit cards, this observation seemed to dispose of the Gypsy influence on the Tarot.

Nevertheless, the whole Gypsy idea was so attractive to occultists that it persisted in spite of such historical inconveniences. In 1889, an influential book on the Tarot would be published with the title Tarot of the Bohemians — the “Bohemians” being, in fact, the Gypsies.

It’s well known today that the Romany people were not descended from the ancient Egyptians, but rather from the ancient Aryan race in India — which could in fact link them to the history of Indian playing cards. And there are various scenarios in which it is possible (chronologically at least) that the Gypsies might have brought Tarot trumps into Europe.

But there is no evidence at all to connect the Gypsies with the Tarot (or with any type of cards) before the 18th century. None.

Although Gypsies were often spoken of as fortunetellers, their specialty, it seems, was palmistry. And when they did begin using cards for divination, they generally used four-suited playing-cards, not the two-part Tarot deck.

The Gypsy/Tarot hypothesis became popular not because there was any factual support, or even a logical foundation. Rather . . . it was embraced and amplified because it appealed to the Romantic imagination, then flourishing throughout Europe.

The kind of fanciful elaboration that linked Tarot with ancient magi or Gypsy fortunetellers was very characteristic of the times. In fact, it was part of a whole cultural style that produced the impassioned music of Chopin and Beethoven, the lush poetry of Keats and Baudelaire, the epic philosophies of Schopenhauer and Nietzsche — as well as a richly imaginative stream of visual art that ranged from the epic paintings of David and Delacroix to the dazzling fantasies of Moreau and Redon.

Perhaps the human need for a sense of wonder and mystery reasserted itself in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, taking many new forms. After a long dry spell of Enlightenment rationalism, all sorts of metaphysical interests were once again pursued, with much excitement. Secret societies grew in influence, magic was studied ardently, great doctrines were proclaimed — and the Tarot, whose potent symbolism and mysterious past were naturally attractive to investigators of the occult, was taken up with enthusiasm.

From this swirl of interest, there emerged perhaps the most influential of all Tarot theorists. And in Part 3 of “The Esoteric Tarot,” there is much to be told about Eliphas Levi.