The Tuesday Newsletter (9.14)

Some reflections on Tarot history + a few sips of Northern Italy . . .

I haven’t forgotten the plan I laid out for September posts—but I’ve been struck by some realizations that I want to share before they become less clear in my mind. So I’m starting here instead.

Over the past few months, I have been revising and updating Part One of The Tarot: History, Mystery, and Lore. The four chapters of Part One trace the history of Tarot from before we have any material artifacts to around 1980. In this process, I’ve had a lot of opportunities to rethink what I wrote thirty years ago.

For one thing, there’s more information now about Tarot history, and of course it’s much easier to access. So part of the process has just been checking facts, making corrections where necessary, and in some cases, adding new information. I’ve also tried to reorganize some parts for greater clarity (and relax the writing a bit), now that I have more space to work with.

But another aspect of the process has been comparing my attitude now to my attitude then. And here are some things I’ve discovered:

I have more appreciation now for the figures who created and elaborated the idea of “esoteric Tarot.” I think I used to see most of them as sincere but misguided, and perhaps a little self-important. Now I see them as remarkably imaginative, and effortful. If you look at their lives beyond just whatever they thought about Tarot, you find they were intelligent, inventive characters, breaking what they believed to be new ground.

Along the same lines, I’m more in sympathy with the aspirants of the Golden Dawn period than I was before. I’d thought of the whole thing as mostly melodrama, mixing personal ambition with fanciful thinking. And there’s some truth to that! But I’ve spent a little time trying to imagine what it might have been like to participate in their activities, and I’m unexpectedly intrigued. I’ve also tried to consider their ideas not from a “modern” perspective, but in the context of what was going on in the world around them at the time.

As a consequence of trying to organize the original text to work better online, I’ve come to see both connective threads and philosophical shifts that weren’t visible to me before. In particular, I see how the Los Angeles group broke from European ways of thinking about Tarot, and combined esoteric ideas with new social developments--like early uses of mass media, and the emerging interest in cross-cultural mythologies and non-Western philosophies.

I’m still processing those reconsiderations, and I might add a sort of epilogue once the revisions are complete. But in the meantime, I want to open an exploration. It’s an outcome of the above, but it takes the form of a big question:

Why would 15th-century painters and courtiers (and/or the designers of print decks, if they already existed) have embellished gaming cards with images like death, the devil, religious figures, a vagabond, a lightning-struck tower?

To mention just some examples.

I never really considered that question before--but I’m wondering now if doesn’t need more attention.

It seems to me that we tend these days to focus on connections between Tarot imagery and other examples of late medieval/early Renaissance iconography—as if that explains everything.

But let’s say for the sake of making a point that the Hanged Man actually referenced the custom of hanging traitors upside down, or even the upside-down crucifixion of Christian martyrs. Why include either reference in a gaming deck?

Similarly—images depicting the ravages of time were widely used in an instructive way, as reminders that worldly pleasures are fleeting. These images often featured bent (hunchbacked) or crippled old men. And death was frequently shown as a skeleton, again to emphasize the grim outcome of our mortal state.

So it’s possible to see a subset of the Tarot trumps as a cautionary tale, like Everyman, an English morality play probably written about the same time Tarot cards were being painted for Italian nobles. (Enjoy a concise summary of Tarot/Everyman parallels from an unexpected source.)

But how, exactly, did any of that fit the idea of a fun evening?

I’m sure someone else has thought about this, and might be offering answers. But I haven’t looked far enough to find them yet--so if you have ideas or can suggest resources, please let me know! In the meantime, I’ll continue sharing my personal speculations about whether we’ve got the right slant on Tarot’s origins.

Note:

This question came into my mind while I was looking through very early iterations of the Tarot trumps, using work found on an exceptional website. Not to be a tease, but I’m going to post a standalone story on this point tomorrow, and I’ll give the link in Thursday’s newsletter.

Lagniappe

I don’t want to leave off this Tuesday SunLetter without a nod to the change of seasons. So here’s something that could be equally interpreted as a send-off to Summer or an anticipation of Autumn . . .

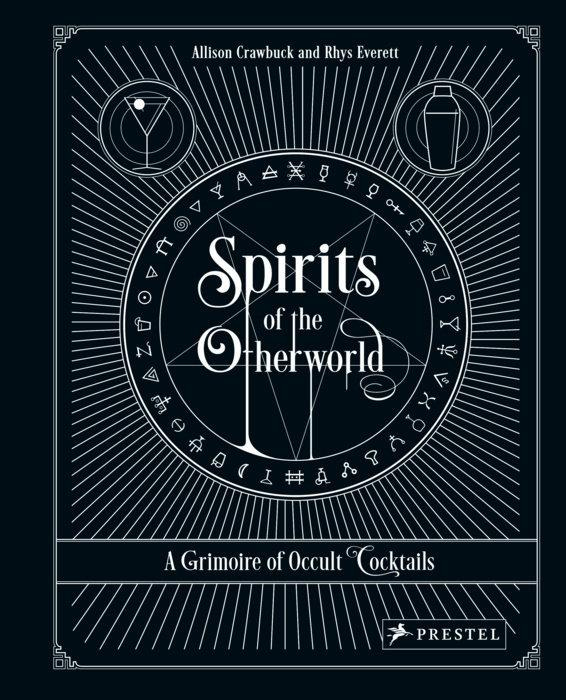

I came across this brand-new book, Spirits of The Otherworld: A Grimoire of Occult Cocktails & Drinking Rituals. Based on brief reviews and a few excerpts, I already like it quite a bit!

Authors Allison Crawbuck and Rhys Everett point out that right around the time Etteila was popularizing Tarot divination in France, “Northern Italy, the region revered for its colorful tarot history was gifting the world with another ritual: the aperitivo.” Designed to awaken the taste buds and excite the appetite, the aperitivo often combines white wine with herbal liqueurs.

Crawbuck and Everett suggest imbibing a “liquid tribute to the Tarot’s early Italian roots,” and they provide this recipe:

Ingredients:

30ml sweet vermouth (Carpano Antica Formula); 15ml Italicus Bergamot; 15ml Campari; 45ml prosecco; lemon twist to garnish.

Method:

Stir all ingredients – except prosecco – with cubed ice in a mixing tin for 15 seconds. Julep-strain into a flute glass, top with prosecco and garnish.

Most of us wouldn’t be able to whip this up from what’s on hand. But here’s my translation for ordinary life, using ingredients you could find pretty easily:

Mix one part Campari with two parts sweet vermouth, shake over ice, strain, and add three parts prosecco (or any brut sparkling wine). Garnish with the lemon twist, and just resign yourself to doing without the Italicus Bergamot. Which by the way is a blend of bergamot orange peel, Cedro lemons (citrons), chamomile, lavender, gentian, yellow roses, and Melissa balm--so you could just use your imagination.

It really does sound like a drink that would go well with Tarot, doesn’t it?

Cheers! And thanks for reading.

Warmest regards, Cynthia

Hi Cynthia,

You ask about why the creators of the Italian Tarot put in images of hanged men and so on in their gaming decks. Co-incidentally,yesterday in an occult bookshop, I picked up a second hand copy of `Tarot: History, Art, Magic`, the catalog of a 2006 exhibition by the Cultural Association of Tarot which is by

Andrea Vitali,an Italian author who addresses this question. Some of his writings have been translated into English http://www.letarot.it/index.aspx?lng=ENG

The Tarot History Forum is dense but has similar discussions,I think.

(sorry if this is a spoiler for your tease!)

It is certainly iconography of the time. Why would they include it in a game?

In a nutshell: Because the whole cultural milieu was infused with Christianity, morality and how to best get into God`s good books.

So they were saying `we are having leisure but we are not forgetting that we are good Christians`.

Also, an idea that occurs to me was that as the tarot was derived in part from the Mamluk decks coming from the Muslim world through North Africa, there was a little religious competitiveness and sense of `if we copy something heathen we will have to put our spiritual stamp on it` .